meanderingexile

The world is a strange and lovely place.

Tainter's Collapse and the Henry Adams Curve

We’re on the verge of 2022. We just lived through the plot of Contagion, and social collapse is in, so it seems as good a time as any to think about the dynamics of it. Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1129552

Complexity, from hand axes to Twitch streamers

Back in 1988, Joseph Tainter published The Collapse of Complex Societies, an insightful look at historical cases of sudden, dramatic reductions in social complexity throughout history. Historians have traditionally explained collapse with a wide range of theories, from the moral decay of ruling elites to more modern ideas of class conflict. While noting these approaches, Tainter builds a model that tries to explain collapse more generally, based off of two dynamics: increasing social complexity, and diminishing marginal returns.

Social complexity is easy to sketch, though challenging to quantify precisely. We can think of it here as related to the number of social roles, and the number of interactions between those roles; some collection of sets on the labels of the social graph. How we define a social role and divide these categories is subjective, and there are many other concepts that might be taken into account: trying to express a numerical social complexity score for a real society is both a monumental task for another time, and unlikely to be useful outside a very specific context.

Just with this imprecise definition, however, we can make comparisons. We might compare a hunter-gatherer society with a handful of social roles to a Bronze Age agrarian civilization with a rainbow cast of characters: farmers, priestesses, healers, warriors, prostitutes, thieves, kings, and jesters. We can compare that in turn to a modern postindustrial society, with its bewildering array of hyperspecialized jobs, clubs, cults, and subcultures. We can then talk about how the latter is more complex than the former, without necessarily resorting to value judgements or whig history.

We can also talk about what happens to complexity as societies change. As new social features of almost any kind emerge, they bring with them new social roles and types of interactions, and increase social complexity. Tainter’s observation was that, as a rule, the complexity of societies tends to increase. New technologies, trades, or crafts beget specialization. New organizations or religions create new relationships, alliances, and conflicts. Governance creates rules, which in turn create specialists - a customs ordnance gives rise to both the customs inspector and the smuggler, each with their respective networks. While roles certainly can be destroyed as they fall out of use, this is less common, leading to a ratcheting increase in complexity over time.

The Energy Treadmill

Like all human activity, maintaining increasing levels of complexity requires energy. At a minimum, this is the simple opportunity cost: time spent performing a specialized, non-agricultural role, or tracking additional responsibilities, relationships, and debts, is time not spent obtaining calories, the primary energy inflow for any pre-industrial civilization. On top of this, almost every activity, whether it be building churches, exchanging letters, or engaging in gang warfare, inherently consumes resources and energy of its own. As a society’s complexity grows, so does its hunger for energy.

This runs headlong into another broad principle from economics: the concept of diminishing marginal returns. For essentially any production process, as some factor of production is increased past some point, the marginal output decreases. This same behaviour is seen in the growth of populations, the spread of epidemics, and a range of other places where we see growth in the presence of constraints. For our purposes, the production process that matters is the tapping of energy flows.

A society can increase the access to the energy under its control through three broad ways. First, it can get access to new physical sources of energy. For most of human history, this would have meant expansion into additional land with farms, livestock, and human muscle power. Second, it can use technology to tap new sources of energy it already controls, ranging from better agricultural practices to hydraulic fracking. Finally, it can use organization, efficiency, and creativity to squeeze more out of the energy resources it already has available.

Speed The Collapse

In Tainter’s model, it is the last process that proves self-defeating, because the increased sophistication in turn increases complexity, in turn resulting in increased energy use down the line. It forms a simple feedback loop, where attempts to improve energy access (potentially for only one actor within a society, or some subset) ultimately drive increased energy consumption for the society as a whole.

Social complexity essentially becomes an input to the energy production process, and follows the same diminishing returns. Random perturbations (whether external like environmental change or internal like social conflict) require problem-solving: this problem-solving produces complexity, increasing demand for energy, which, among other things, prompts more complexity.

If this feedback process is not periodically bailed out by access to new energy sources, either through innovation or expansion, then the system eventually enters a dangerous regime, where the marginal energy profit from increases in complexity is declining. Rather than dividing up the benefits of growth, individual agents are now fighting over a shrinking piece of the pie to maintain the status quo. The social ability to collectively solve problems is compromised. Shocks from perturbing events travel further and hit harder. Eventually, if this process continues, collapse is inevitable, when one of these shocks becomes too hard. Typically, this either means military defeat, where the society is subsumed by a competitor, or dissolution, where subgroups walk away from a relationship that has become a negative-EV proposition.

Like every model, this is an oversimplification of reality, but I think it’s a useful lens to keep in your toolkit. As mentioned above, classic explanations of collapse will often talk about things like a loss of civic virtue, class or ethnic conflict, or failures of environmental management. While those are deserving of study, Tainter’s model explains the diminishing-returns, dog-eat-dog circumstances that can inflame those issues.

Highway to the Danger Zone

The above was a summary of Tainter’s ideas. Below, we enter my own baseless speculation; please adjust priors accordingly.

Energy is an interesting parameter to think about in a lot of different systems. In a pure physics context, understanding energy flows often lets you predict quantities of interest without having to dig into the messy dynamics. That’s especially tempting when we move to models of human systems, where modelling the dynamics is often next-to-impossible, if not flat-out so.

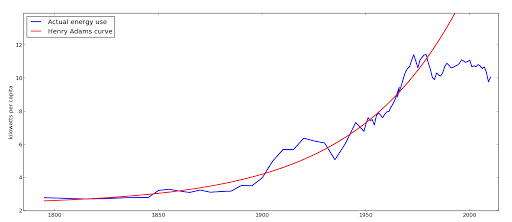

With that in mind, it’s useful to turn to our own, modern situation. A vocal advocate for measuring (and increasing) human energy use is the futurist J Storrs Hall, who popularized the idea of the “Henry Adams Curve”. The Curve is a fit to US energy consumption, going off of data from the US Energy Information Administration. From the beginning of the dataset in the late 18th century to the 1970s, the curve roughly fits a 7% year-on-year increase in energy consumption per capita. However, following the oil shocks in the early 1970s, the data changes. Although US energy consumption continued to increase, so did population, and so per-capita energy usage flattened out. Contra mainstream ideas about the virtue of efficiency and reduced energy use, Storrs Hall, a techo-optimist, argues that this failure to secure an increasing energy supply underlies a wide range of social ills and failures to meet desired standards of living in the United States and beyond. Graph of Henry Adams Curve by R Storrs Hall, from the blog post “The Henry Adams Curve: a closer look”. URL:http://wimflyc.blogspot.com/2021/01/the-henry-adams-curve-closer-look.html.

The underlying methodology isn’t necessarily bulletproof. In particular, I have questions about what the data measures; one of the hardest bits of understanding any complex real-world system is figuring out where the system boundaries are. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that a lot of the energy consumption going into the goods and services consumed by Americans past the 1970s was simply happening overseas, off of the EIA’s books and distorting the picture.

For collapse afficionados, though, just the possibility of diminishing returns on our energy sources, for whatever reason, technical or social, should get your attention, because of what the Tainter model says about the tendency for that situation to enter positive feedback. The pandemic years have made supply shocks a part of life, from the ridiculous, self-inflicted toilet paper shortages to the grim overload of global healthcare systems. The reasons behind those individual failures, and the processes that lead to them, are fractally complicated. Without going into the details, there is broad theme of lack of capacity, of systems being stretched thin.

Is it a coincidence that we are seeing these thinning processes come to a head just as our twentieth-century energy flows seem to be reaching their limits? Viewed through this lens, a range of themes- aggressive financialization of the economy, the dominance of the online/tech sector, diminishing infrastructure quality- are not causes but effects, existing downstream of the growing, percolating pressure on every agent to compete in the face of a declining energy share. Efficiency improvements, like profitable yet fragile just-in-time logistics systems, are intensification as coping strategy, trying to squeeze more out of less, at the cost of increasing complexity. Tainter, of course, has dire words for the ultimate outcome of this project.

I should be clear that this isn’t even a hypothesis, at this stage- just a speculation, maybe a feeling. It’s unclear how we’d go about estimating an appropriate complexity curve, and energy consumption data going back more than a few decades is patchy, at best (the eternal problem of cliodynamics). It’s very possible that we have the arrow of causality backwards, and a failure to secure sufficient energy resources is downstream of greed, moral failure, a Marxist crisis of capitalism, or any number of other competing root causes. It may simply turn out on further reflection that the statement is simply ill-posed; we should, as always, be suspicious of hedgehog theories, especially when it comes to something as sophisticated as the arc of civilization.

Unordnung

If it turns out that this process is in play, however- if we are entering or have entered Tainter’s domain of declining marginal returns and fragility- then it would imply at least two big points, that I think are worth reflecting on as we watch the coming years play out.

First, to get to a better place, we’re going to need a lot of energy. As our population and standards of living both continue to rise, alongside the ratcheting increase of social complexity, we know that we’re going to need more. If we’re already past the point of declining marginal returns of energy, we’re going to need a lot more to break out of the point where the majority of increasing access to energy is needed simply to maintain the status quo. Historical examples of doing this successfully include things like territorial doubling or the deployment of coal and oil. We need to be thinking about order of magnitude increases in available energy, not simply trying to match current use to population growth curves. This is not a panacea; the awe-inspiring complexity of human society and the problems thereof isn’t going anywhere. It may, however, be a necessary relaxation of constraints to make those other problems solvable.

Second, until that happens, don’t count on things slowing down. I don’t know anyone who thinks the last few years were normal by any definition; pick your arena, from domestic US politics to the global wooden pallet market, and something “unprecedented” has been happening, thanks to the interplay of technology, politics, and the forces of history. Many of these individual narratives are seemingly transient, and give some hope that things will eventually calm down. If the complexity-energy crunch is real, however, that underlying civilizational macro force isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, and you should expect that as soon as one bizarre arc plays out, another one will pop up to take its place.

There are no brakes on the Weirding. Stay cool, give thanks to the gorilla, and always have an escape plan.