Apollo and Automation

Mindell’s Digital Apollo is a great book, and not just for the space-obsessed. Spaceflight was intertwined with the development of cybernetics, modern control systems, and the digital computer. Re-reading it recently while recovering from an illness, I found certain themes especially resonant: specifically, the role of human beings in semi-automated systems, and the nature of human control.

Spaceflight emerged from two, often dueling, engineering traditions: missile builders, who were used to building entirely automated systems, and aviation, which treated instruments as tools for the pilot, and at the time (the 1950s) was only begrudgingly admitting the role of autopilots as a way of enhancing the pilot’s capabilities.

These two groups would go back and forth about the appropriate role of humans in each system. The missileers, exemplified by everyone’s favorite German hobby rocketry pioneer Von Braun, viewed the humans as little more than cargo, once even floating the idea that the astronauts should be sedated for the launch. The pilots, meanwhile, wanted to literally fly the rockets off the pad, only gradually ceding this ground when simulations (another cybernetic technology) proved that for Buzz Aldrin to steer a Saturn V into orbit with a stick was, by any reasonable standard of reliability, impossible.

With the technology of the time, there were some valid arguments on both sides, especially when midcentury electronics and automation struggled with reliability issues. Fundamentally, though, the argument was philosophical, and indeed emotional; the astronauts wanted to fly because they were pilots, and flying was what they did.

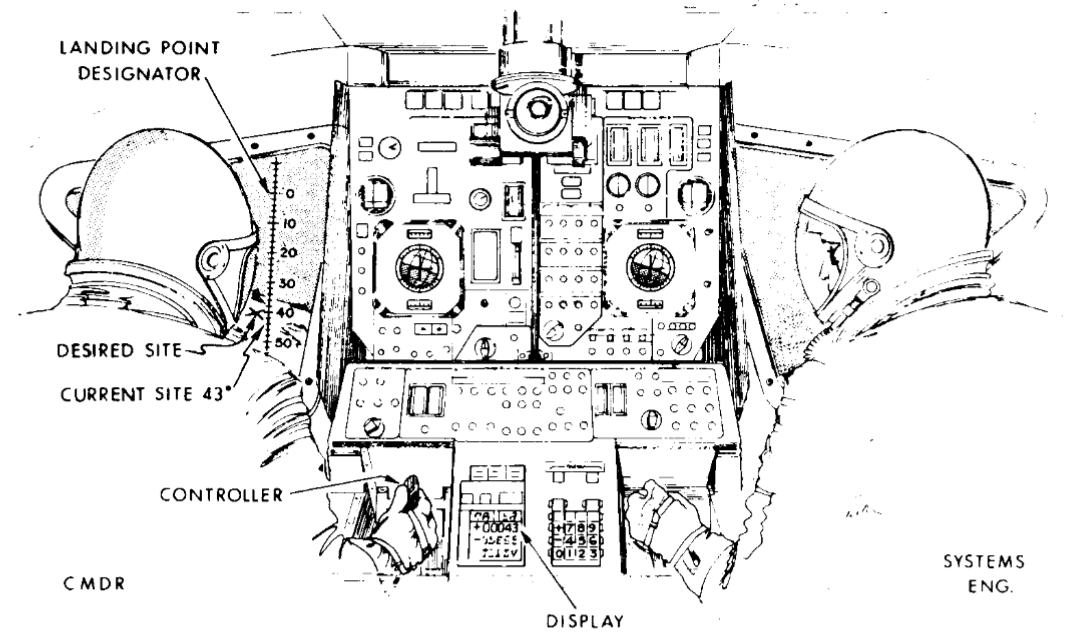

In the heroic saga of the Apollo missions, this struggle found its synthesis in the lunar landing phase. As the LEM approached the lunar surface, it had to execute a complex series of control operations and burns, mostly controlled by the (incredibly novel) Apollo flight computer. At the same time, as it got close to landing, it had to choose a landing site. This involved an unknown and somewhat unpredictable interaction with the lunar topography, much more complicated than the mathematically elegant guidance problem of a booster arcing into orbit, a challenge for the sensing and signal processing techniques of the day.

The result was a centaur system, where the pilots commanded the LEM’s onboard computer in two ways: commands entered into a keypad through a noun-verb structure, and control inputs through the sticks that steered the reaction thrusters by digital control loop. While an early (and now somewhat endearing) argument that astronauts should approve each computer instruction before it was executed didn’t come to pass, the astronauts did have the ability to both command the computer and provide approval at critical checkpoints before the automated procedures progressed. Instead of a silent black box taking control away, the computer became another instrument to master, and another way of expressing and demonstrating skill.

This solved the problem: both the nominal problem of getting down on to the lunar surface, and the philosophical problem of making sure that it was done by an American astronaut-pilot with his hand on the controls. This gave us one of the central stories of heroic Apollo legend, when Neil Armstrong took control of the final stages of the Apollo 11 landing, guiding the Eagle over a field of boulders that satellite surveys had missed. Practiced skill, fine motor control, and nerves of steel carried the day.

The technology only progresses in one direction, however. Fifty years later, terrestrial aircraft carrying passengers land under automated control all the time, with the pilots only providing nominal supervision. This comes with its own problems (erosion of skill, and as tragically seen in Air France Flight 447, hand-off issues when complex automated systems try to abruptly pass control back to humans). UAVs are everywhere, and pilots and engineers debate the shrinking role of human pilots. Eventually, fully automated aircraft seem inevitable; but “one day” can be a long way off, and in the mean time, aircraft have to fly.

Now, as I’m writing this, the same programmers that encroached on the pilots' sacred domain from the Draper Lab at MIT are now going through the same experience themselves, and the same arguments play out. We have automated systems that can replicate many of the programmer’s traditional roles, though they often struggle when interacting with complexity and system boundaries. Some embrace their new roles as supervisors for these systems, enjoying the power they bring with them. Others raise objections about reliability and dependability; with some reason, but with an undercurrent of identity threat. Programmers want to program because they are programmers, and programming is what they do.

It doesn’t take a lot of foresight to predict that for a while, at least, we

will see centaur systems, with humans driving clusters of agents, Claude Code

or one of its successors. These systems will be somewhat automated, but not

quite: a human will step in to approve or disapprove at critical steps,

preventing disaster from a stray rm command. Sometimes they’ll jump in

directly with a series of surgical edits, feeling like Armstrong tapping his

RCS thrusters as they tap vim sequences to guide things into place. The

approaches that succeed will be effective, certainly, using humans to make up

for the limitations of the automated systems, but they will also be the ones

that provide an opportunity for skill, and virtuosity.

Until such a time comes as they can be removed from the engineering process entirely, human beings will need to be there to guide things, and while they do, they will want to fly.